In ‘The Unreliable Ledger’ (17-27 September 2025), an exhibition at the no/mad utopia gallery, the curator(s) assembled works under the rubric of remembering and forgetting (both gratefully and purposefully, or reluctantly and forced). The exhibition was put together in collaboration with the Beirut Printmaking Studio.

The exhibition and its artworks are resolutely analogue. In that regard, they are documents, but they don’t record in the way that ledgers, bureaucratic files, and photographs are generally supposed to—they’re unreliable. The exhibition showcases various approaches in relation to how we understand memory, and to wider problems of memory within a critical and cultural discourse. Often the artworks call on the imagery of remembrance (childhood, family, mementos, and photos) that suggest the transience of life, and the partial quality of memory. For the most part, these seem like reliable records of the unreliable experience of memories that are firmly in the past; they are a storehouse that is searched with some awareness of loss.

Tarek Mourad’s All Walks of Life: Plate I (fig. 1) exemplifies an indexical approach. Photography is famously indexical, created through a mechanical process of light on chemically-treated paper, but it is the soles of the shoes themselves that really demonstrate it. They are marked by use, and the marks signify many kilometers walked and burdens carried. The shoes are displayed on black backgrounds, positioned centrally, and in clear cut, well-focused black-and-white. They are specimens, and specimens are always examples of types. These mass-produced and widely available shoes actually tell us little about who wore them, where, or when. Here, memory is a trace left behind and imprinted — willingly or unwillingly, and reliably or unreliably. The prints of Fanny Bikaz also seem marked by the things themselves.1 Thus, the plate has become the memory, and printing is the process of recalling the memory to mind. However, Bikaz’s images offer only anonymous shapes, because memory is never sure.

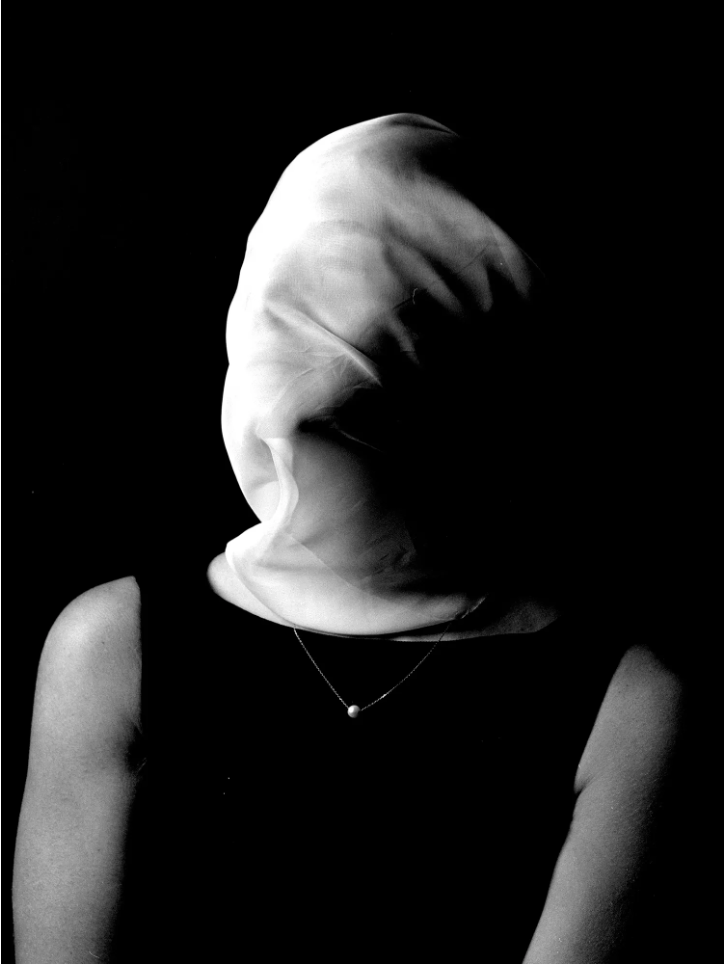

In Mira Diab’s series To Remember or to Forget (fig. 2), sitters are shrouded, but are otherwise presented in a portrait style. Conventionally, portraits, directly or indirectly, address the viewer. However, in this case, the profound black of the background merges with that of the clothes, severing the head and arms like the fragments of ancient statues. The darkness is so complete that the singular pearl of the necklace hangs as if suspended in nothing, and the head becomes a barren rock in space. The effect is to depersonalise the unnamed sitter, abstracting and concealing them like draped artefacts in an abandoned museum. The classical beauty of the image, its abstraction, and the apparent sun-bathed peace of the sitter sets it in contrast to the alienation it expresses. Like Cindy Sherman’s photography, it feels like we must have seen these before but cannot remember where or when. The sculpture-like busts have life and expression; they are beautiful, but suggest memory that is mysterious or entirely lost.

These artworks hold up the fissures and sutures of memory to scrutiny. As a purely subjective experience, this is a worthy and interesting enterprise that offers avenues for self-reflection and critique. They are part of a tradition in which the subjective is presented in opposition to the authoritarian empiricism of the bureaucratic state and its technological ideology. Mostly, they are not undertaking the more obviously political questioning of public memory in the way that post-civil war Lebanese art often invested in the counter-factual and fictitious to question and problematise the dominant narrative.

Salah Missi’s, Big Enough (fig. 3) is a startlingly simple image. It presents, isolated in a resplendent white page, a tombstone-like doorway revealing a cloudscape ready to cross into the pristine and fragile space of the page. The unassuming print represents the all-too-common and reluctantly recalled memory of smoke. The dark menace of the image in the blank of the page creates the feeling of fixation and is suggestive of the silence of smoke in contrast to the preoccupation with sound experienced during war. The doorway isn’t itself represented, it is clear only in the limits of the representation of the plume, in precisely the way that our fears and anxieties define our view, and our cherished spaces of so-called safety are built out of nothing. It seems to encompass the inside and the outside of disaster, the moments before and after, and the utter absence of definition between the two. Indeed, there is no outside, the white page is a constituent of the trap that draws us in. In its small and isolated image, it suggests the limitations of the experience and yet also its all-embracing domination — the tombstone is unavoidable.

It reminds me of a passage in Sigmund Freud’s “Beyond the Pleasure Principle” (1920) in which the membrane of a single-cell organism is discussed.2 In Freud’s article, the membrane protected the cell from over-stimulation but also trapped things inside. He uses it as an analogy for consciousness, which represses and anxiously prepares us for unknown disasters. However, some things get through the barrier, or are produced inside it, and then we are stuck with them. Inside the calm, the interior is roiling.

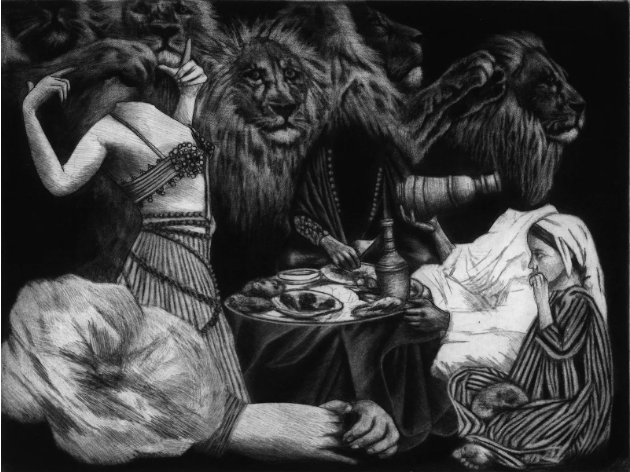

In Freud’s formulation, the faculty of memory is created as a response to the formation of the reality principle, and is used to truth-test claims in the present against memories of the past. However, he concedes that memory is still linked to the pleasure principle and thus prone to represent wish-fulfilment rather than reality.3 It is an unreliable tool of empiricism. In that regard, memory is surprisingly close to dream, and thus Sabine Delahaut’s Save the Last Dance for Me (fig. 4), with its surreal combinations of headless participants, dancer, meal, and watchful lions, seems appropriate in its ethereal non-reality.

Forgetting is always the corollary of memory, and completes the contradictory binaries of recall vs loss; and record vs wish-fulfilment. According to Freud, nothing is ever forgotten; it remains in the unconscious to become the material for dream, or is repressed. Repression, of course, produces pathologies which must be “worked through”. Forgetting is thus conventionally understood, both by the bureaucracy of state and law, and in the psychoanalytic sense, as negative. The agent of the state and the psychoanalyst work to recover the lost talisman of memory, they are both archaeologists of a sort, who will not let relics rest.4

In Hesiod’s Theogony, Memory’s children are the nine muses (poetry, dance, music, history etc), and among them, they know everything. Without them, we have no knowledge or truth, we have no witness or testimony, we have no shared experience or solidarity, and we have no projects. If we follow the reasoning of John Locke, without memory, we have no self. And in Plato’s work, knowledge itself is actually the recovery of forgotten memories (anamnesis) from our soul’s existence in a perfect metaphysical realm that pre-existed this material reality. In other words, if we can recall it, memory can help us understand, and thus return to utopia. If we are to recapture a future, we must adequately recall our past. However, the pop-culture version of postmodernism’s repetitive self-referentiality leaves little room for the past or the future. It suffers from a surfeit of memory, and the compulsion to repeat that traps culture into a cycle of pastiche from which we cannot move on.

Freud posits that all instincts aim at restoring the animal to a state before an external force disturbed it. Since the inanimate preceded life, this proposition leads Freud to the conclusion that “the aim of all life is death.”5 Reasoning by analogy: the anamnesis, the forgotten utopia that we yearn to return to, is a kind of death—or at least is accessible through death. And this is the mood in the death’s heads of Samer Bou Saleh’s Head I, II, and III (fig. 5). These placid still-lifes, with their everyday objects and rich lighting, effect a gorgeous baroque and a quotidian mood simultaneously. There’s something delightful and almost funny about them, a ghoulish monster-movie style plus an awareness of the long tradition of contemplating mortality. The conventional emblem of vanitas, the skull, is here fleshy and alive: it is alive in this recurrent but subverted motif. What are we to make of mortality undone, of what seems such a contradiction, the decapitated living? Its liveliness does not imply that there is no death; indeed, death is clearly signified, but the object of our attention is returned to the living. Arguably, death has always been inaccessible to the living, but these images render even its contemplation inaccessible, and the life that we can contemplate in its place is “decapitated”. In Bou Saleh’s photographs, there is an adaptation of a long tradition that turns the redemptive possibilities of prayerful engagement with the vanitas into a contradictory trap—a living-death without a redemptive escape. There is no future, no life when we have no memory, no anamnesis or utopia. These images neatly encapsulate the undead of a postmodernity trapped in the compulsion to repeat, searching for a way of “working through” the past.

The exhibition is a counterpoint to a world increasingly orientated towards the plugged-in abstractions of the virtual. We are slipping towards the neon-noir dystopia of cyberpunk and our lives often seem real only in their online and digital manifestations. It could be argued that the exhibition’s media (print and analogue photography) and its subjects (which eschews any images of our technological and digital present) are themselves forgetting the now. They attempt to maintain in the present a past that is actually only a memory. These artworks invite the viewer to join the artists in haunting the past, to dwell in it and sift through it, to find in it meaning that it may not have to give.

It seems that, like the rest of us, the exhibition does not know how to move forward, we are unable to break the cycle of the compulsion to repeat. In the current critical climate, we resist the imposition of the empirical, we deny and rebel against the documentary and the objectifying mentality. We look back to grasp vanished certainties that cannot give us the direction we seek because memories are unreliable.

Exhibition Details

The Unreliable Ledger

17 - 27 September 2025, no/mad utopia gallery, Beirut